Wonder Knows the World

A Christian Doctrine of Creation, Part 2

“Isn’t it wonderful?” John Moriarty

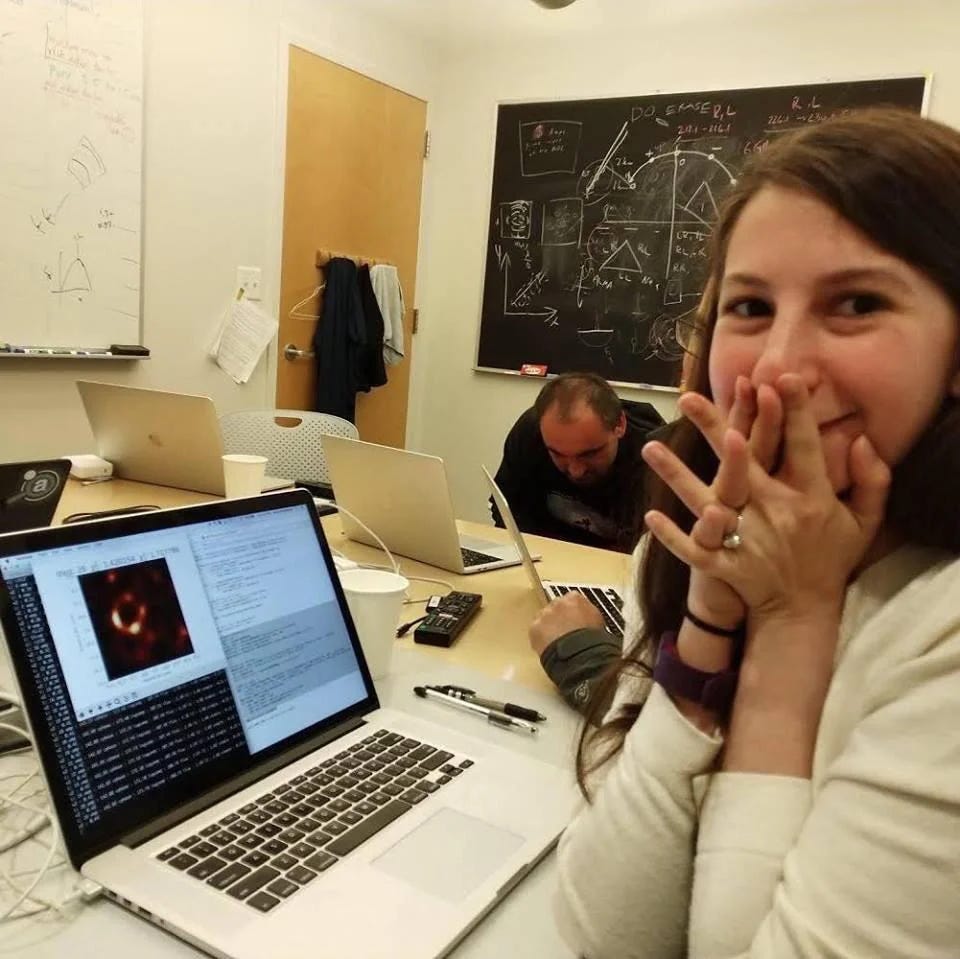

What strikes me first are her eyes—they are wide with wonder. She interlaces her fingers in front of her chin, a posture of barely suppressed glee. On the computer screen beside her is the cause of all this excitement, though perhaps it’s not immediately obvious why: a blurry red ring on a black background, like something from Tolkien. The first photo ever taken of a black hole. The woman is Dr Katie Bouman, one of the scientists and computer engineers connected with the Event Horizon Telescope that captured the image. This was the first time in human history we have been able to observe a black hole as it sucks light and matter into itself. For Bouman, it is a moment of wonder.

This particular black hole lives at the centre of the M87 galaxy, some 55 million light years away. It is incomprehensibly massive, measuring 40 billion km across. Our entire solar system could fit within it, with plenty of room to wander about and stretch. We are looking at something that strains our capacity to understand. And it’s not even the largest black hole. That record currently belongs to the black hole that powers quasar TON 618, though we have only begun to look. That black hole has a mass 66 billion times that of our sun, and eleven solar systems could fit inside it rubbing shoulders. Almost daily we learn something that staggers our capacity to understand.

We live in a great age of discovery. Technology and science have given us insight into our incomprehensibly large and wondrous cosmos. Consider the images beamed back to us from the James Webb Telescope since its launch on 26 December 2021: vast star fields, ring nebula, cartwheel galaxies, massive cloud formations of dust and gas stretching light years, auroras above the poles of Jupiter, galaxies colliding in the far, dark reaches of space. And these are only a small fraction of the great, incomprehensible number of objects in space.

I am beginning this series on the Christian doctrine of Creation by naming some of our experiences as modern people that shape our questions, concerns, and anxieties as we ask about creation. In my last post, I named grief as one significant experience. But alongside grief, we must also name wonder. To be a modern person alive to the world is to feel wonder at our place in a staggeringly large cosmos.

Wonder is a complex feeling. The word comes from the Old English cognate of the German for wound—suggesting a breach, a rupture in established meaning. In wonder, we encounter something vast or powerful or impressive that makes us feel small in comparison, something beyond our capacity to understand or easily fit into our ordinary ways of seeing. We are wonder-struck—unsettled or moved by something we can’t fit into our normal frame of reference.

Deep space is a cause of wonder for modern people, but so too is deep time. Before the development of the science of geology in the 18th century, the creation of the earth was understood as a relatively recent event. 9 am, Monday 26 October 4004 BC was the calculation James Ussher, Archbishop of Armagh, arrived at in 1650 through a “careful” “study” of the Bible. Ussher’s calculation was still printed in English bibles until the early 1800s. On such a time scale, earth’s history appears coterminous with human history and takes from it its meaning and purpose.

But this is not the world most of us now live in. Modern science sees the age of the earth as around 5 billion years and of the universe as 13.8 billion years. This awareness of deep time—the sheer, overwhelming scale of it, of the year upon year stretching back into the incomprehensible reaches of the past—is hard for us to get our heads around. Deep time, "the immense arc of non-human history that shaped the world as we perceive it," is a cause of wonder. We are left reeling, as though we stand on the edge of an abyss. Human civilization appears only as a blip in the larger project of the universe, the “skin of paint” at the summit of the Eiffel Tower, in Mark Twain’s arresting analogy.

Deep space and deep time are sources of wonder for modern people. As is the beauty of the world.

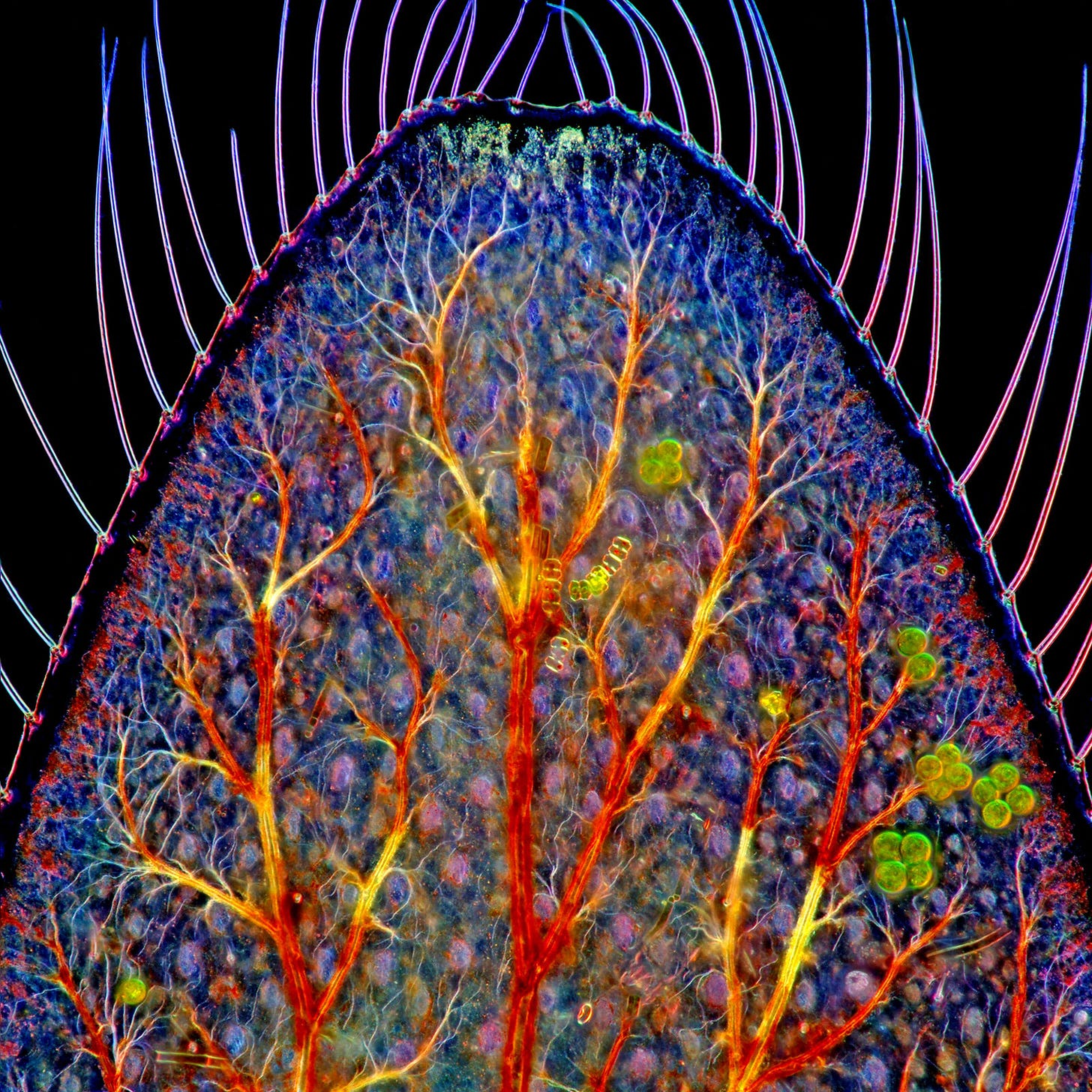

Consider this:

It is a photo of the caudal gill of a dragonfly larva at 25x magnification using a polarised filter. Modern camera technology has exposed us to a world soaked with beauty, extravagant with it. We may well have lost intimate knowledge of the natural world (researchers in the UK have found that children are “substantially better” at identifying Pokémon “species” than “organisms such as oak trees or badgers”). But on my screen, I have seen the rings of Saturn lit by an eclipsing sun, the iridescent scales on a butterfly wing, the soft burnish of copper crystals, the deep blue of the feathers of a plum-throated cotinga; I have heard the mournful melody of whale song and the buzz, ping, and pew of ice freezing on a lake in Sweden. I have marvelled. To be a modern person is to experience wonder at the beauty of the world.

Deep time, deep space, and the kaleidoscopic beauty of the world are all sources of wonder and raise questions that a Christian Doctrine of creation must address: Why is there so much beauty in the world? Why is the universe so large and so incomprehensibly old?

Catholic theologian Matthew Levering put the questions well, asking

“why a wise and good God willed to create dinosaurs to rule the earth for more that 150 million years and then disappear, to create the sun as merely one among many octillion stars, and to create countless species of which 99.9 percent are now extinct. Why would such unfathomable multitude and such strange diversity, seemingly purposeless, absurd, and wasteful, characterize God’s plan for creation?”

If our doctrine of creation is to be of any help, it must address these questions. And that’s what I plan to do through this series. But I also want to suggest that wonder not only raises questions but is a deep intuition—a felt, pre-rational sense—of the nature of reality.

Consider the contrast between wonder and its sister feeling terror.

Johannes Keppler, one of the great astronomers of the scientific revolution, and one of the first men to study the universe through a telescope, wrote this confession about contemplating the infinite universe:

This very cogitation carries with it I don’t know what secret, hidden horror; indeed one finds oneself wandering in this immensity, to which are denied limits and centre and therefore also all determinate places

The novelist John Updike wrote this about the revelations of modern science.

We shrink from what it has to tell us of our perilous and insignificant place in the cosmos … our century’s revelations of unthinkable largeness and unimaginable smallness, of abysmal stretches of geological time when we were nothing, of supernumerary galaxies … of a kind of mad mathematical violence at the heart of the matter have scorched us deeper than we know.

Terror responds to a cosmos experienced as immense, hostile, indifferent, and meaningless. A world in which we are alone and adrift. Wonder intuits a different world. In wonder we encounter something vast or powerful or impressive that startles us, something that interrupts and unsettles our ordinary ways of seeing or knowing, that makes us feel small in comparison. But unlike terror, in wonder what we encounter seems not absent of meaning but full of meaning, full of value and significance. Wonder senses the great worth of what we contemplate, even if we don’t understand it. The object of wonder appears to have weight. And this weight—this sense that there’s something here, something important, something of value—is not something we feel we project onto the object (we cannot conjure wonder). It seems to exist in the object, independent of us. In wonder, the world feels saturated with meaning. We feel caught up in something; we sense a mystery, a meaningful though hidden reality, at the heart of things. The opposite of Updike’s mere “mad mathematical violence.”

This is why wonder has long been understood as both the end and the beginning of learning. Wonder creates a “longing to know.” We feel there is something to be discovered, something worth knowing that we don’t yet understand. We feel beckoned. Wonder gives rise to curiosity—wondering.

As we explore the Christian doctrine of creation, I will suggest that it is wonder, not terror, that rightly responds to the truth of our world. Wonder is an intuition into the true nature of reality. The Christian doctrine of creation names our world as full of meaning, beauty, purpose, and value not of our making. Wonder not terror knows the world right.

Grief. Wonder. Our doctrine of creation must help us make sense of these deep experiences, the questions they raise and what they might intuit about our world. There is a third dimension of the modern experience I want to name: longing. To be a modern person alive in the world is to be suffused with certain longings as we relate to the other-than-human world.

That’s the topic of my next post.

"[Wonder] seems to exist in the object, independent of us. In wonder, the world feels saturated with meaning." This is radically refreshing - as opposed to the common invitation for humans to make our own meaning.

As I read this, the development of the nuclear bomb came to mind. Many of those scientists describe feeling wonderstruck at the immense power that had been contained, something previously behind imagining. I guess the difference is they were ‘wonderstruck’ by their own wielding of power over nature.